Petropolis: Aerial Perspectives on the Alberta Tar Sands

Canada / 2009 / 43 minutes

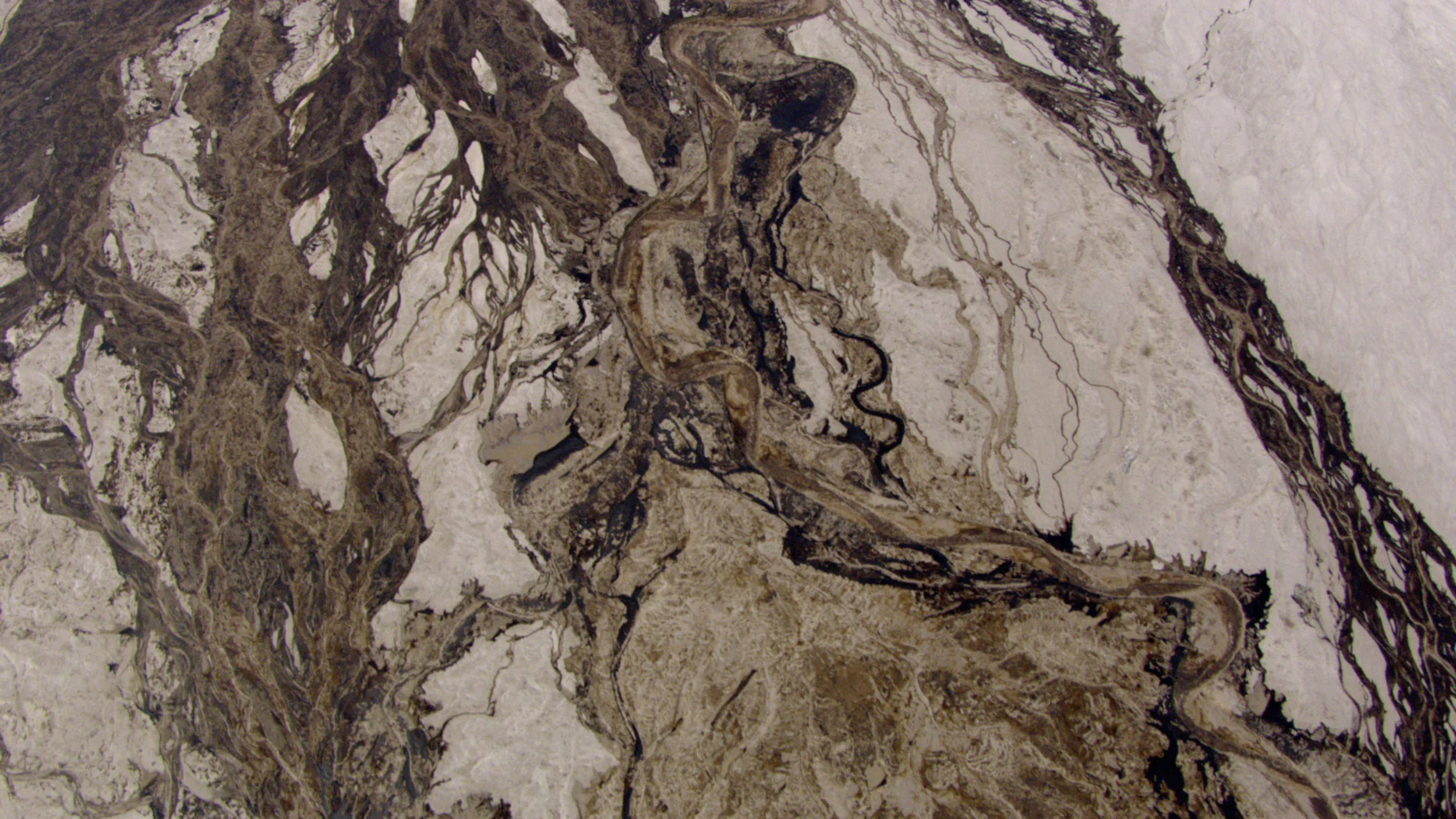

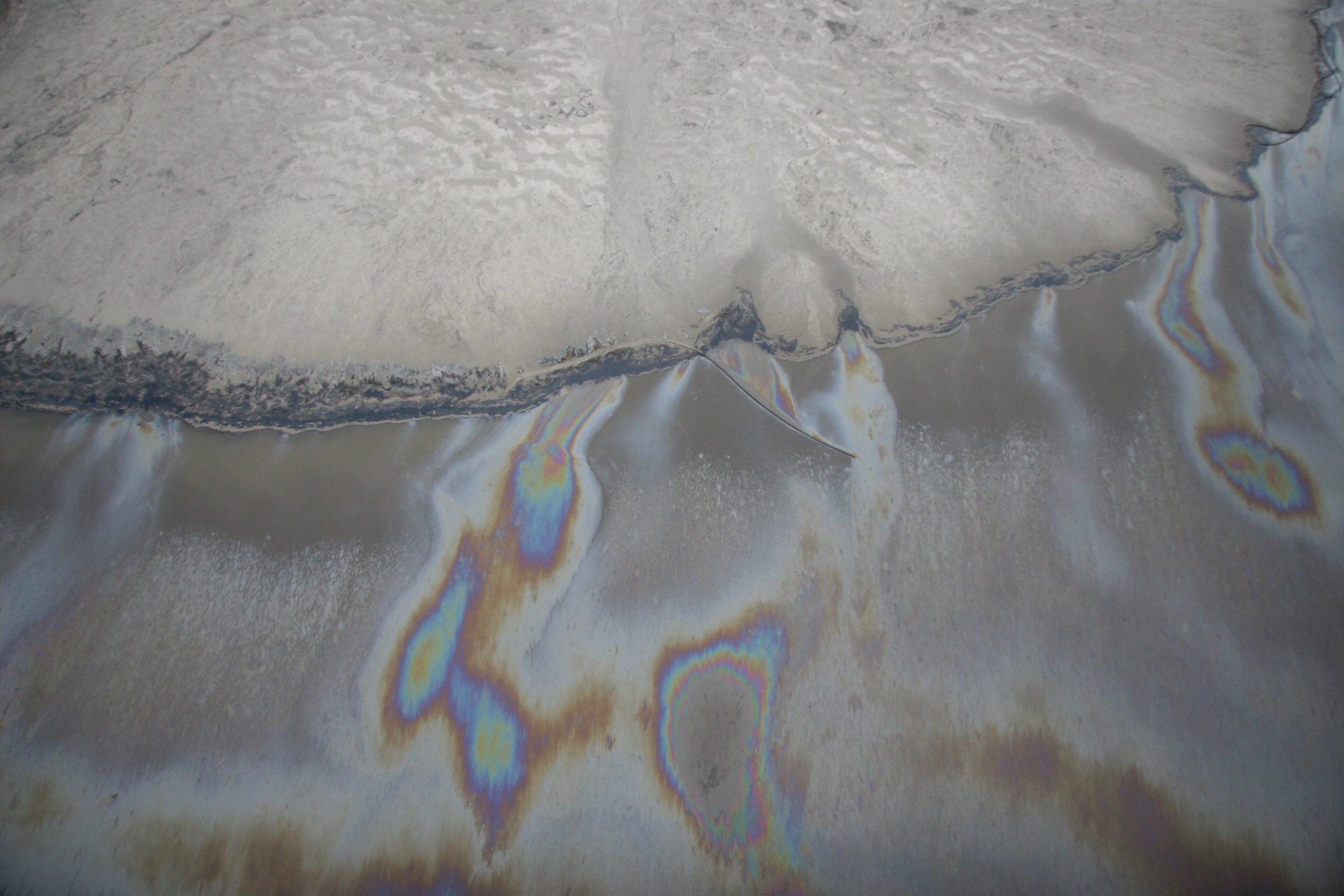

Shot from a helicopter, Petropolis: Aerial Perspectives on the Alberta Tar Sands offers an unparalleled view of the world's largest industrial, capital and energy project. Canada's tar sands are an oil reserve the size of England. Extracting the crude oil called bitumen from underneath unspoiled wilderness requires a massive industrialized effort with far-reaching impacts on the land, air, water, and climate. It's an extraordinary spectacle, whose scope can only be understood from far above. In a hypnotic flight of image and sound, one machine's perspective upon the choreography of others suggests a dehumanized world where petroleum's power is supreme.

DISTRIBUTION

Worldwide theatrical distribution; presented on Arte Television in Europe; Netflix and VOD release.

Rent or purchase ON Vimeo On Demand

Rent or purchase on iTunes (Canada)

Stream on Doc Alliance Films (Europe)

Purchase on DVD

REVIEWS

“Simply by flying over the Athabasca tar sands and capturing both the natural and industrialized environment, Peter Mettler creates an ecological horror story that's also a highly watchable excursion into abstracts of colour, form and texture… Twisted shapes and sickly hues fill the screen; when Mettler pans to include something recognizable, we realize the immensity of the industrial blight.” ★★★★★ – Andrew Dowler, NOW Magazine

"Strikingly beautiful and presented in such confident, assured rhythms that you're almost hypnotized by the flow of images – until you realize you're watching grand-scale systematic destruction." ★★★★ —Norman Wilner, NOW Magazine

"Mettler's visually dazzling aerial coverage of the devastation caused by the Alberta tar sands project resembles one vast moving Ed Burtynsky photograph." ★★★★½ —John Griffin, Montreal Gazette

"The problem with one of the most alarming post-apocalyptic settings you'll ever see in a movie? It's real." ★★★★ —Kevin Williamson, Toronto Sun

“A must see film… A spectacle of astonishing and terrifying beauty, a toxic landscape of myriad earth tones, a canvas that’s been gouged and scraped and scumbled as if by a giant palette knife, and painted with iridescent swirls of jade and topaz. Pollution has never looked so pretty. Petropolis is a motion picture oil painting, literally.” - Brian D. Johnson, Macleans

"A sumptuously shot aerial view of an ecological disaster, the Alberta tar sands. Using footage he created looking downward from a helicopter, Peter Mettler has created his own plaintive moving-image version of photographer Ed Burtynsky's politically engaging work."—Marc Glassman, The Globe and Mail

“The film is less an apocalyptic vision of environmental destruction than it is an exploration, a series of discoveries… Like Mettler’s previous epics of exploration Gambling, Gods and LSD and Picture of Light, Petropolis is a work animated by the powerful desire to discover the unknown, and but by an equally powerful humility before the formidable challenges that this unknown throws up against our senses and the technology that seeks to extend those senses.” – Jerry White, Cinemascope

"Finds both horror and strange beauty in man's capacity to force nature to bend to his skewed vision."—Peter Howell, Toronto Star

"A gorgeous, affecting and deeply cinematic eco-documentary… something of a movie miracle."—Kevin Maher, The Times

"It's heartbreaking when it hits you that the overall visual experience of Mettler's film is like the journey of a bird, following a river route and then suddenly spotting strange creatures below as it searches for a place to land."—Jennie Punter, The Globe and Mail

“One of the best films you will see anywhere this year, it's urgent, powerful filmmaking and should not be missed.” – Jesse Wente, CBC Radio

“The most devastating thing you will ever see.” – Neil Young

EXCERPTS

Petropolis: Aerial Perspectives on the Alberta Tar Sands (2009) – Condensed Version

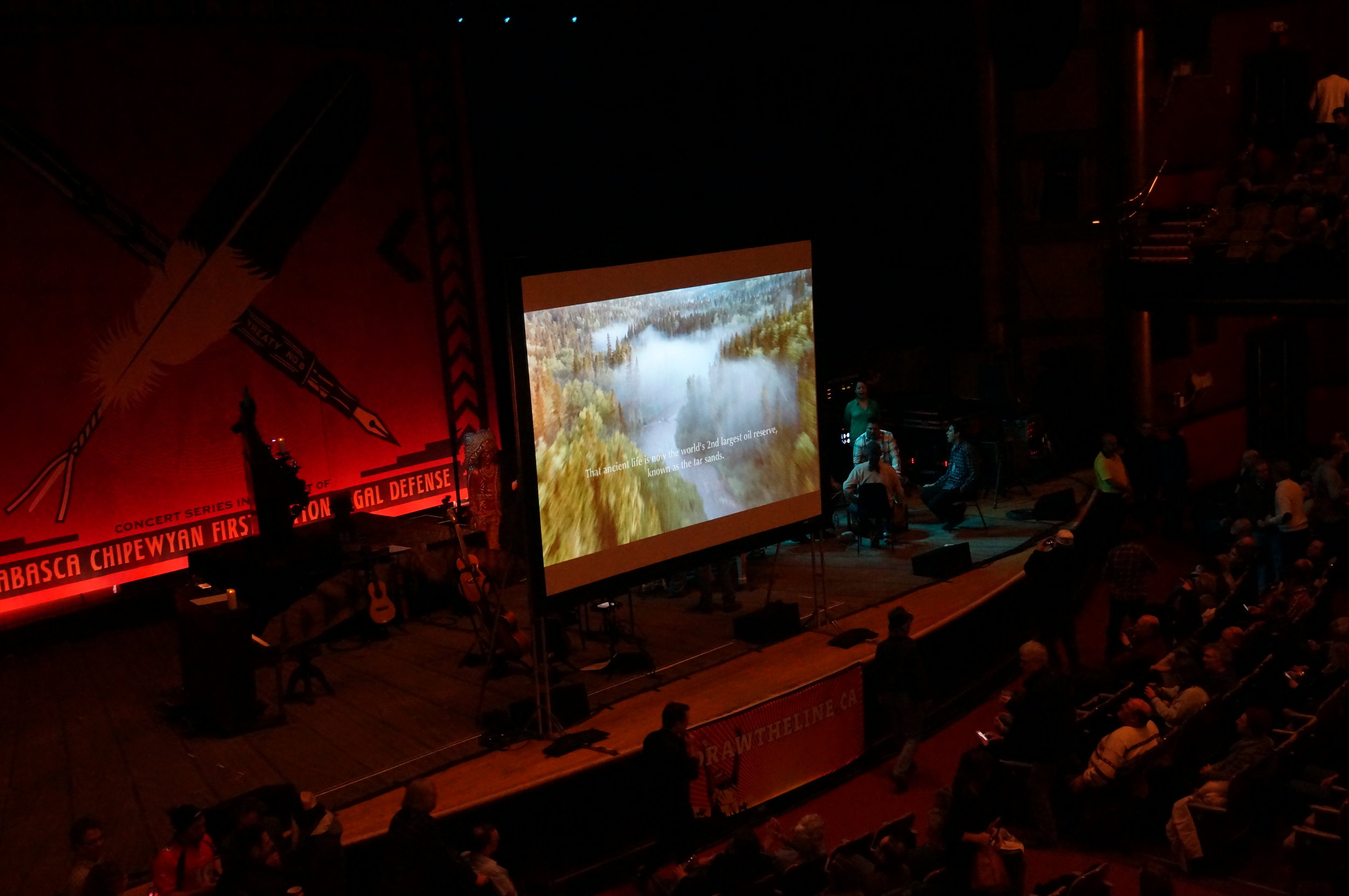

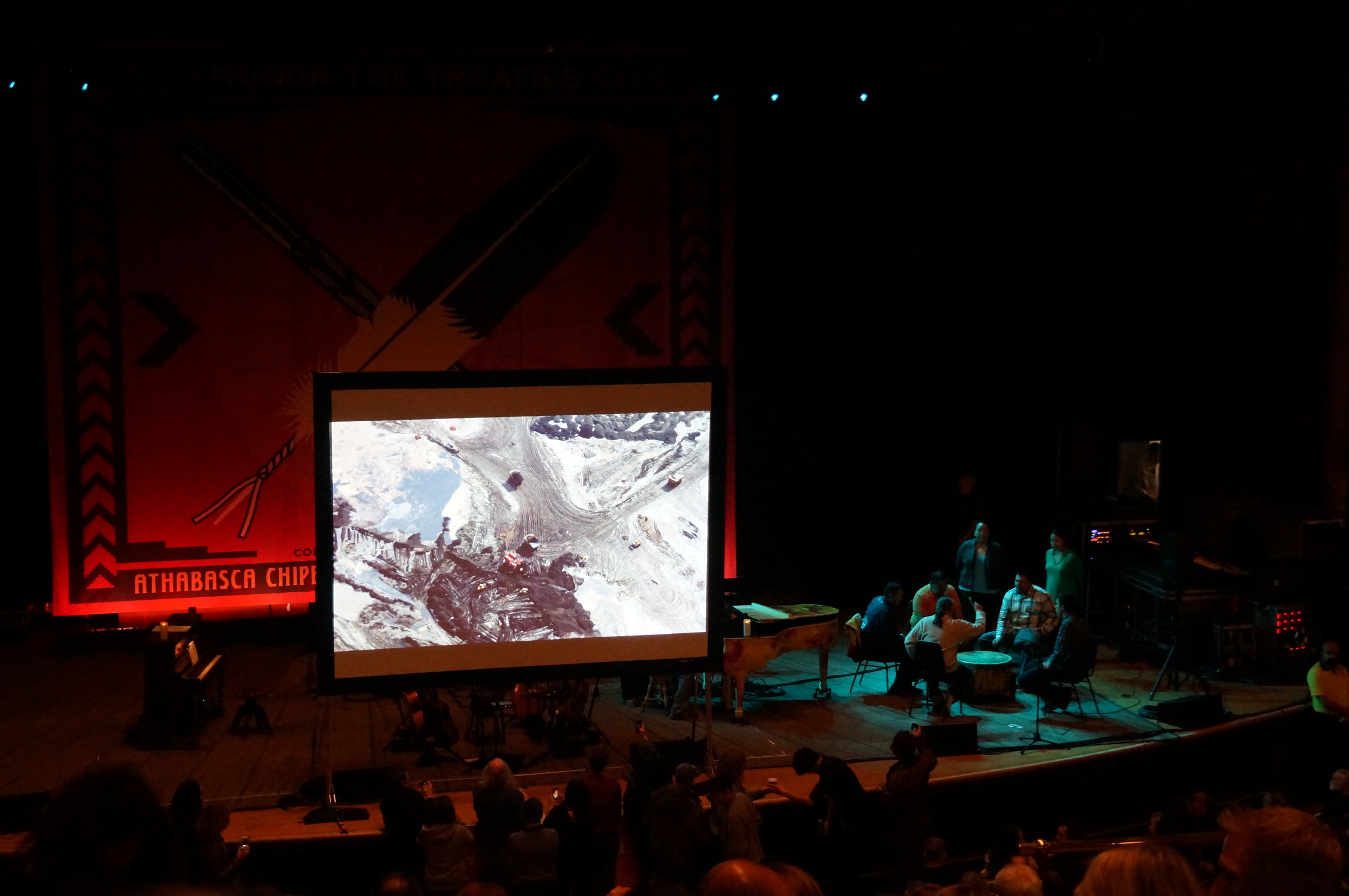

Produced to accompany Neil Young's "Honor the Treaties" concert tour in 2014.

FILM STILLS

PRODUCTION STILLS

Images from the Toronto performance of Neil Young’s “Honor the Treaties” tour at Massey Hall (2014). “Honor the Treaties” was a four-concert tour to raise environmental awareness and money for First Nations people affected by the rapidly expanding Alberta oil sands development.

INTERVIEW WITH PETER METTLER ON THE MAKING OF PETROPOLIS

Why did you make Petropolis?

I’ve always been interested in the way we humans have the ability to create technology out of our given natural environments. My impression is that the technologies we develop are also part of “nature” and should be managed ecologically, as part of the system that is in fact, life itself. I have long been amazed at the disrespect towards our own home, our own bodies, in relation to garbage, pollution, destruction, etc. It seems that we may live within a crisis of perception, in that we are somehow able to disregard the harm we induce upon our own selves through our actions. I’m interested in demonstrating the effects of some of our lifestyle choices – or perhaps more accurately – the lifestyles imposed upon us by a rather avaricious economic system, with its short-termed interests.

In exploring the nature of consciousness and seeing, I’ve been making films that try to immerse an audience into an experience of something in which they must also confront themselves. The viewing experience becomes more of a meditation around a subject than strictly an absorption of information. In previous films I’ve explored subjects like the northern lights or culture in Bali, but in some way they always explore the inter-connectedness of things and how we perceive them.

There has been a lot of debate about the tar sands, but the opportunities to actually see and somehow experience them have been rare. There is a lot of information readily available out there, from a variety of perspectives, but nothing that really lets you “feel” it. The beauty of cinema is that it can deliver an experience at least somewhat close to the real thing - in this case though, seriously lacking the smell. I was in the process of researching the tar sands for my own next feature [The End Of Time], which in part explores clouds and what goes into them from the ground. A fortuitous request about cinematography came in from Greenpeace at the same time and things evolved from there. We all agreed on the importance of simply showing the tar sands to our own country and the rest of the world, in the interest of sparking constructive discourse.

Are the tar sands what you expected?

I was expecting some rather gargantuan smokestacks – which I found. But they were dwarfed by the size of the rest of the vast open-pit mines and tailings ponds. The industry that we actually physically saw was dwarfed once again by the comprehension of the potential size that it could become if fully developed. And it didn’t stop there. As one begins to understand many of the ramifications and issues entangled within the tar sands development, it becomes mind-bogglingly immense and important. It is not only a manifestation of our current oil-based lives but also one that reflects our current consciousness and values.

What did you learn during the making of this film?

This would be a very long answer, perhaps another film, or a book – of which there are already some good ones for further reference. But to be succinct, in a kind of random point form, I’d say – a lot of statistics and factoids, and how this all impacts not only the environment, but also economics, community, drug abuse, immigration, wildlife, international relations, territorial conflict, free trade agreements, consumer lifestyle, health, climate change, Native American culture… and the list goes on to implicate the intricacies of our daily living, our media and as I said before, perception itself. I put the word “perspective” in the title because indeed that is what was offered to us in the process of making this film – a perspective on a situation, that when considered in an associative way, has an immense importance in relation to so many aspects of our lives.

Did you ever consider the irony of shooting Petropolis using a helicopter powered by fuel?

Yes, that conundrum was immediately apparent to me. Our little helicopter machine seemed like a small child-insect hovering over its food source while other giant petrol-powered machines moved around masses of oil soaked earth below. It’s reminiscent of the bees with their hives and food supplies of honey. In Fort MacMurray, there was an abundance of oil culture too. A large amount of vehicles were on the roads at any time, the smaller vehicles tended to be SUVs. Plastic and fast-food were in abundance. Sea-dos raced aimlessly along the river. So much seemed fabricated, temporary and disposable. The town seemed to serve mostly the boom of the economic moment, predestined to become like one of those earlier gold-rush ghost towns. Also, we mustn’t forget the medium we work with ourselves – video and film – its machines, plastics and processes are all part of Petropolis.

Is shooting a film from the air more challenging?

Every film is challenging, whether shooting in a helicopter or a canoe. The greatest challenge is trying to capture a cinematographic vision that pertains to, and is imbued with, the character or essence of the subject. In this case, it was very clear from the ground that we can’t actually see much. The companies won’t even let you shoot from the side of a public road, let alone invite you into their facility. But even if they did, there would be no way to understand scale and relationships. So in some respects the content determines the form, and the form determines the technology. In this case we needed that overview and we needed long shots to show what sits next to what: the upgraders by the tailings pond, by the river, across from the mines etc.

A particular challenge was to present this topography to the viewer. As soon as you edit shots together the tendency is to see a construction of images. We tried very hard to not edit too much, rather letting the camera explore details then panning or tilting to reveal the horizon or relationship to the big picture. We respected the 1000 foot altitude limit of private airspace and thus worked with a considerable zoom lens that was mounted on the nose of the helicopter controlled remotely with joysticks and dials. Inside, the pilot and the operator Ron Chapelle sat in the front while I sat in the back with a preview monitor. I could talk to them both through headsets and thus could help direct and anticipate the flow of shots. We had about 3 hours to do everything. In the editing we then used some of the robotic characteristics of the camera moves and various adjustments to emphasize the idea of machine looking at machine.

Are projects like the tar sands inevitable?

Well, they are already here. We have indeed already made ingenious uses of many natural resources throughout a relatively small period of time - but without caring much for the associated perils. I don’t think that anyone ever set out with the deliberate intention to destroy themselves. Most of our development has been done in the interests of making life better, easier, nicer. However, too little attention has gone into industry and technology as ecology – into seeing the whole global, or even universal, picture with all the interplays. There has been too much emphasis placed on financial profits rather than sustainability of the most valuable commodity – life itself.

It’s a good thing that we are hearing more thoughts about this from thinkers and scientists in the last few years. Perhaps for the first time we are actually in a position to collect enough information and knowledge to actually have a full enough perspective at all. Yet serious action needs to be taken quickly and the onus is not only on the consumer, but even more so on the governments and corporations that devise the lives we lead and things we consume. Something needs to give. Anyhow that’s my humble filmmaker’s perspective – one of millions, I’m sure…

What do you expect the impact of the film to be?

I think the film has fallen into a unique position in that it has combined the resources of Greenpeace, as a large well-informed enlightening institution, with the resources of a filmmaker, and his associated vision and cinema audience. Ideally this will cross-pollinate the audiences. I think that what the film shows could be shocking to some people. Ultimately we see it as a catalyst for discussion and as a conduit to more information. The rest remains to unfold.

CREDITS

Produced by Greenpeace Canada in association with Grimthorpe Film Inc.

Director and Writer: Peter Mettler

Aerial Camera Operator: Ron Chapple

Editor: Roland Schlimme

Original Music: Gabriel Scotti, Vincent Hanni

Sound Design: Peter Mettler, Roland Schlimme

Producers: Sandy Hunter, Laura Severnac

Executive Producer: Spencer Tripp

AWARDS

Prix du Jury du Jeune Public, Visions du Réel

Genie Award Nomination for Best Short Documentary

Screened at numerous international festivals including Toronto International Film Festival, Vancouver International Film Festival, Film Festival Ghent, Festival Dei Popoli, Sheffield Doc Fest, England, Canadian Front Film Series at MoMA, Hong Kong Film Festival, Rotterdam Film Festival, Buenos Aires International Film Festival, Art Gallery of Hamilton.