The End of Time

Switzerland/Canada / 2012 / 114 minutes

Working at the limits of what can easily be expressed, filmmaker Peter Mettler takes on the elusive subject of time, and once again turns his camera to filming the unfilmmable in The End of Time. From the CERN particle accelerator in Switzerland, where scientists seek to probe regions of time we cannot see, to lava flows in Hawaii which have overwhelmed all but one home on the south side of Big Island; from the disintegration of inner city Detroit, to a Hindu funeral rite near the place of Buddha’s enlightenment, Mettler explores our perception of time. He dares to dream the movie of the future while also immersing us in the wonder of the everyday. The End of Time is at once personal, rigorous and visionary. Peter Mettler has crafted a film as compelling and magnificent as its subject.

What is time? A reality? An illusion? A concept? These questions lie at the heart of Peter Mettler’s The End of Time.

In 1960 an American astronaut named Joe Kittinger jumps from a balloon at the edge of space. Although falling at the speed of sound, he feels suspended in time until he approaches the clouds and is returned to the context of earth. Before the opening credits are complete, Mettler has established the scope of The End of Time, which will offer perspectives at once cosmic and very human. Drawing from science, philosophy, religion and the personal, the film chronicles a journey into the nature of time, while bearing witness to this perilous period in the history of the planet.

Beginning at CERN, the particle accelerator in Switzerland, Mettler meets with scientists probing regions of time that we cannot see. By smashing particles together at almost the speed of light, these experiments hope to reproduce conditions just instants after the Big Bang. But the scientists are still not sure: is time real, or is it only a perception?

Back at home in Toronto, Mettler connects us to felt time, and the grace of its everyday passage, before continuing on to explore the island of Hawaii. Although the islands are comparatively young, the vastness of geological time is made manifest. Hot lava forms new land masses before our eyes. An awesome power, driven by “this engine called earth,” lava spares only a single home on the south shore of Big Island, inhabited by a man named Jack Thompson, who lives outside society’s construction of time.

Even without cataclysms, it becomes clear as the film turns to explore the urban decay of Detroit that our culture and installations are vulnerable to nature in only a matter of years. “The earth will heal itself. Humans will be gone and the earth will live on,” remarks Andrew Kemp, an urban gardener re-building homes in an abandoned inner city neighbourhood. Auto factories are mausoleums, and the workshop where Henry Ford invented the Model-T – perhaps the most radical of our “time-saving” technologies – is now a parking lot, after a stint as a movie theatre. Meanwhile, the electronic music producer Richie Hawtin reminds us that when you’re “with your machines, it’s a very personal thing.” Hawtin, who lives “on the edge between now and tomorrow,” connects us directly to the tree of Buddha’s enlightenment and the philosophy of the present, in Bodhgaya, India.

“If you have a beginning, then there’s a problem, but if it’s beginning-less, then there’s no problem,” Rajeev says. Yet we are inevitably “entangled in the idea of time.” The body, Mettler reminds us, is transient. A Hindu family carries their dead relative to the outskirts of town, where they burn him on a pyre. As the corpse quite literally goes up in smoke, we are returned to the cosmic perspective, and an observatory in Hawaii, on Mauna Kea.

From the obervatory, we encounter cosmic time. Earth occupies a “very quaint neighbourhood of our galaxy,” and, from this point, our planet has been able to evolve a life form which can think about thinking. The telescope is the best time-machine we have invented to date. With it we can look up to 10 billion years into our past. As the film remarks, “We are the universe looking at itself.”

And with that Mettler dares to dream the future. When he returns us to earth, it is back to his childhood home where his mother evokes in us one of the most direct, human experience of time – watching those you love grow old. A conclusion which leaves little doubt that if we take care of our responsibilities in the present – moment to moment – then the future will take care of itself.

DISTRIBUTION

Screened at numerous international film festivals; worldwide theatrical release; broadcast on TV in North America and Europe; Netflix and other VOD.

Rent or purchase ON Vimeo On Demand (World)

Rent or purchase ON Vimeo On Demand (USA)

Rent or purchase ON iTunes (Canada)

Stream ON National Film Board of Canada

Stream ON Artfilm.ch (Europe)

Stream ON Guide Doc (Europe)

Stream ON Hoopla (USA)

Purchase a copy on DVD or BluRay

REVIEWS

"A form of cinematic meditation ... powerful, moving and sensually ravishing to watch." – Geoff Pevere, Toronto Star

"Recalling the work of Terrence Malick, Werner Herzog and the late Chris Marker... The End of Time becomes immersive and hypnotic... a ravishingly beautiful experience." – Stephen Dalton, Hollywood Reporter

"Peter Mettler's ruminative, frequently astounding essay film doesn't just contemplate time's relativity; it aims to cinematically embody it... Time is on this extraordinary doc's side." – Eric Hynes, Time Out

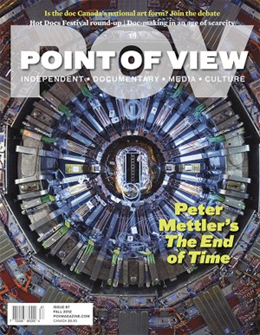

"A work of vision... A globe-trotting cine-essay about time... poetic and lovely." – Adam Nayman, Point of View Magazine

"Mettler's trippy films work as perceptual experiences... free your mind, and the rest will follow." – Mark Peranson, Pardo Live Locarno

"Traverses the globe to explore (and explode) our conceptions of time, in this entrancing combination of documentary and mind-expanding philosophical speculation." – Steve Gravestock, TIFF

"One of Canada's great cinematic experimentalists returns with a documentary exploring the meaning of time... There is not a hint of the didactic here, but rather pure contemplation… a timeless, meditative state for viewers." – The Globe & Mail

"Splendiferously trippy!" – Jason Anderson, Cinemascope

"Peter pushes forward with every new film, in his bid for a re-visioned consciousness." – Philip Hoffman, filmmaker

"Mettler has tuned himself to the world. Always receptive to the unexpected." – Peter Weber, novelist

"One of the year's best films, The End of Time isn't something you simply watch; it's something you surrender to." – Peter Howell, Toronto Star

"This mesmerizing documentary uses images and sound to observe time and make our understanding of it palpable." – Paul Ennis, Canada's Top Ten

"To call it a documentary is misleading... Cosmomentary would be a more appropriate name for the genre Mettler is pioneering." – Brian D. Johnson, Macleans

"The End of Time explores an impressive array of ideas related to humankind's relationship with time. Better yet, it does so while providing an uncommonly intense degree of audiovisual stimulation - leave it to Mettler to make lava flows seem impossibly sexy." – Jason Anderson, The Grid

"Mettler approaches time as might an alien who s come to Earth for the first time..." – Angelo Muredda, Torontoist

“Visually-stunning and remarkably thought-provoking.” – Christian Williams, Utne Reader

EXCERPTS

STILLS

SELECTED PRESS AND INTERVIEWS

“Nothing But Time,” review by José Teodoro in Film Comment

“All Things Must Pass,” review by Adam Nayman in Point of View

“Lost In The Moment: Peter Mettler on The End of Time,” interview in Cinemascope

“Peter Mettler’s The End of Time is the Ultimate Trip,” review by Brian D. Johnson in Macleans

“Snow, Sex Chairs and the Hadron Collider: The Films of Peter Mettler,” Nonfics, 2013.

“Mettler L’Alchimiste,” special issue of 24 Images, Issue 157 (Fall 2013).

“Keeping in Real Time with Peter Mettler,” Derivative blog, February 26, 2013.

Kevin Ritchie, “Mettler’s Time arrives in Toronto,” Realscreen, September 6, 2012.

Interview with The Seventh Art at TIFF, 2012

Interview with Cinetfo, 2012

Interview with Northernstars, 2012

Interview with Canadian Film Review, 2012

Peter Mettler Q&A at RIDM 2012

Peter Mettler and Philip Gröning in Conversation, 2015

INTERVIEW WITH PETER METTLER ON THE END OF TIME

Why did you call the film The End of Time?

It’s referring to the end of the idea of time, not to the end of the world. Although the end of the world reference is of course interesting, given that it’s 2012, the year the Mayans believe the world will come to an end. I think our species has never been more aware of our place in the big picture of time than now – but it also begs the question: What is time anyway?

So how would you describe what The End of Time is about?

Ultimately, I suppose it’s a film about perception and awareness. It offers a challenge to see through our conceptual thinking. We use concepts like time to organize and understand our lives. We use our created languages to define our world. But these things can also end up controlling us and disconnecting us from the “real” world, or the “non-conceptual” world, or “nature” – whatever we might choose to call that which is beyond words.

The film first tunes the viewer into concepts of time, but then leaves the world of ideas and takes them through an experience of time, which is not unlike that of listening to music, with the intention to provoke a heightened awareness and associative thinking process, and the realization of the impact of our actions on the future.

It does seem like a very ambitious way to handle a very ambitious subject for a film. What was it that made you want to take it on?

I never had any intention to try and solve the puzzle of time. That, of course, would be absurd. I didn’t want to try and explain past and current concepts of time, because even that is a rat’s nest I don’t have the will or wherewithal to sort out. While researching, I explored geology, archeology, astronomy, biology, shamanism, philosophy, and so on. There’s far too much to try to do a comprehensive survey of human thinking about time. And I wasn’t going to try to explain Wittgenstein or particle physics.

I wanted to observe time using the tools I’m most comfortable with: images and sound. I wanted to observe time using the time machine of cinema. Specifically, I wanted to explore what we mean when we think of time, and how we experience it. It was important to me to get some perspective on the idea that time may not even exist. And subconsciously or inadvertently I now know that I was still on the path of exploring transcendence, as I did in Gambling, Gods and LSD, and coming to terms with mortality and the fact that everything ‘dies’. More than being my profession, filmmaking is the way I interact with the world and try to understand it. It’s the way I explore and learn about things that fascinate me. And time fascinates me.

What camera did you use to shoot The End of Time? How long did it take to shoot?

I shot the film with a Sony EX 1 and Canon 60D. They are quite small and portable compared to the film cameras I’m used to, and allow for more flexibility, spontaneity, the ability to record good quality stereo sound, and the option to trek for miles through nature.

The project took five years from first ideas to final print in 2012. I shot on and off for three of those years. We filmed the CERN sequences in Switzerland during development because they told us that if we waited, the particle accelerator would be turned on and it would become a lethal, magnetic, radioactive, zero-degree-Kelvin environment where protons collide at the speed of light!

I know it sounds odd, but along with reading extensively about the subject, development consisted of spending a lot of time with the camera observing nature. It was helpful to really pay attention to seasonal transitions and all their implications – watching time pass. When I started shooting in a more formal way, I had developed a list of subjects I was interested in. But it continued to be a process of exploration and discovery, following leads and associations. For example, I knew I wanted to go to Hawaii, to shoot lava, because of its direct relationship to the ancient processes of the earth – lava’s such a wonderful, animate example of geological time. But I had no idea of who I might meet in Hawaii and want to interview. Once I heard about Jack, the man whose house is surrounded by active lava flows, I sensed that his circumstances could cross several themes in the film, so I made an effort to go visit him.

How did you hear about Jack Thompson. Is he still there in his house?

I heard about Jack through a long chain of associations – meeting one person who tells me about another person, etc. That’s often how I find things to shoot. And actually, very recently the volcano – or the goddess Pele, as the Hawaiians call it – wiped out his home after 30 years of flowing all around it. He was safe. Big Island is the youngest in the chain of Hawaiian Islands, at about half a million years old. They were all created from cooling magma breaking through the crust of the earth. There’s another island, Lo’ihi, coming up 20 miles off shore, due to surface in 50,000 years. But, as Jack says: “That’s too much to think about…”

I spent weeks wandering the landscape finding recently submerged forests, houses and even a school bus. Jack lived in a subdivision that had been otherwise entirely buried by the lava flows, its other inhabitants having fled long ago. His lone house was visible from the air and he’d become a sort of legend. He lived alone like a hermit on an island, happily cut off from modernity for a few years, before the lava got him too. It was one of the most serene and crazy places I’ve ever been.

You shot in Switzerland, Toronto, Hawaii, Detroit and India. How did you choose where and what to shoot

At some point, as I was researching experts and possible subjects, it became clear to me that time is everything. I could look at anything and see time acting upon it, or through it. I could shoot anything, really. As George Mikenberg, a physicist at the particle accelerator in CERN, says: “Time means: we are.” So, to me, it became more a matter of how to look at things.

Cinema is a perfect tool for looking at things with an accented approach or slightly skewed perspective. That became most important – shooting with an awareness of the present and of our seeing, regardless of the subject. I trusted that if I followed that in the shooting and editing, it would manifest in the film, on the screen. And I actually think it does.

So I chose subjects from my endlessly long lists that would offer good exploratory experiences around some of the notions of time that seemed noteworthy. That’s how I came up with CERN and the Mauna Kea Observatories, looking into the conditions of the Big Bang and deep space, or the first life on volcanic rock, or the observing of animals and wondering about how they might experience time, and so on.

So how long did it take to edit the film?

The edit took about two years. Some editing was happening while I was still shooting. For example, my co-editor, Roland Schlimme, worked on assembling the CERN particle accelerator footage while I was shooting in Hawaii. There were intermittent periods when I stopped shooting altogether and just hunkered down in the edit room on my own. Roland would cut some scenes and I would cut others and then we’d piece them together, divining a structure. In some cases this helped me figure out what could be shot next.

The India sequence was actually directed from the editing table. I asked Camille Budin and Brigitte Reisz, who were traveling to India anyway, to gather material at the site of the descendant of the ancient Bodhi tree, where Buddha experienced his enlightenment. They did an excellent job. Giving them specific questions and thoughts to consider in choosing subjects, as well as specific images, was very different from the exploratory shooting I like to do on my own. But I had shot in Bodhgaya on two occasions already, so I had some idea of what I wanted.

At a certain point I took over the editing and sound work entirely. This often happens with the editing of my films. It becomes very intense, even personal, and I can no longer give an editor direction. I need to handle and cut the material to find the optimal relationships and to finish. At the same time, all the notes I’d been making in development and shooting started to get honed towards formulating a voice over.

It takes a while to know what the expressed meaning of a particular sequence is, or will be. Like Colonel Kittinger, the man who falls from space, becoming emblematic of time stopping, or Richie Hawtin, the musician with his machines experiencing a singularity while performing – meanings are buried in the mass of possibilities which the material offers and must be sculpted out to fit as part of the whole.

Towards the end, Alexandra Rockingham Gill gave input on story structure and voice over. Peter Braker helped to fill out and mix the foundation of sound that Roland and I had created during picture editing. Throughout the entire process, sound, image, and text were all worked simultaneously until the final architecture was found.

Who are the people we encounter in Detroit? Can you explain further what is going on there?

The people in Detroit are part of a community that purchased an entire block of abandoned houses for very little money in the middle of a largely destitute neighbourhood. They have created their own vegetable gardens, fixed up their homes, and are part of a new generation with an alternative approach to city living.

In Detroit, I was interested in seeing the transitioning eras, which are remarkably visible there – the old opulent movie theatre, which is now a parking lot but was once the site of Henry Ford’s workshop, for example. Nature is reclaiming the city in places, demonstrating its power to continue on without us. And you have these people with a new vision inhabiting the ruins of the automotive industry dream – the factories of which are still strewn around, picked over for sheet metal or other resources.

Detroit also gave birth to the ever-expanding music movement of techno or electronic music. We visited with Richie Hawtin who played an important part in this evolution, having migrated weekly across the river from Windsor, Canada, in the early days. To me, techno is emblematic of the digital age, which has sprouted out of this old industrial-dream city.

Although the film is made up of a variety of components and styles, it all fits together into a seamless whole. Can you describe how you choose juxtapositions and structure? What kinds of logic do you use in putting shots together?

I follow what I believe is the logic of nature and human experience. Organic logic – the unfolding of events, the associative pathways our lives and pursuits take – rather than succumbing to pre-determined structures. So much work today is designed to fit formulae and genres, it loses its connection to the way things really go. And the way things really go is what creates uniqueness in humans, and art, and nature – and it’s what offers up all the most compelling stories.

Our existence and our being is unbelievably complex. Studying nature makes it so clear. There are so many pathways that any living or moving thing can follow, so many pressures it’s subjected to. Just watch lava making its way down a slope. That says it all in the most fundamental way – as it slides and twists along the path of least resistance and burns up anything soft in its path.

Do you see The End of Time as being in the tradition of other kinds of films? Which ones?

What I’m working at with my last films has something to do with becoming aware of the forces of nature. I’m trying to integrate practices of seeing with the use of image-making technology into that. I still don’t know for sure how to answer the question: Is cinema part of nature? Although my sense is that everything is nature and even technology helps nature become aware of itself.

Certainly I have been influenced by what has come before – the work of Johan van der Keuken, Chris Marker, Cinema Verite, Antonioni, the 1960s avant-garde, Expressionists & Dadaists, lots of TV and a good scientist friend. I see the traces of all this in my work. But I hesitate more and more to even call it my own work, because I’m also aware of how the trails of history meet unconsciously inside of us. The times and technology are crucial in determining our visual language.

That intensely sensorial section near the end seems to be partly about technology. It’s quite a departure from the rest of the film. What were you trying to achieve with it?

We call that section of the film “Mixxa.” It’s partly the result of several years of collaboration with Greg Hermanovic of Derivative Inc. to create a performance image and sound mixing software. It mixes together images in the way sounds and music were mixed in the past. The mix of several layered tracks of images are performed and recorded in real time to create a type of audio-visual rendering which was not really even possible just a few years ago. I implemented this in The End of Time to create a sequence that, at one level, works like a flow of consciousness suggesting several parallel realities. The early part of the sequence includes a composition by Bruno Degazio and Christos Hatzis called “Harmonia” – a beautiful mandala-like depiction of harmonic overtones thought to be key to understanding the inner structure of the universe by Plato, Plotinus, all the way to Johannes Kepler and Sir Isaac Newton.

In the 1890’s, the Lumière Brothers’ first cinema inventions started with long takes and static shots cut together head to tail. That’s what the technology suggested and allowed. The Lumières’ camera capturing the train pulling into the station was a first step. Now, through various media, we can see in layers, we can see back in time. We see many things at once, in quick succession. Instantly. We see mixes and associations. We see great works of art from the other side of the world juxtaposed with a photo of our best friend at a BBQ. Technology has tuned us to see in such ways. Our minds and bodies continue to be conditioned by the technologies we use. Our very consciousnesses – the way we think, see, and dream – are profoundly affected.

There is very real talk about multiverses. If there are such things, one day we may be able to see into them. We have developed ways to see with technology what our eyes cannot, be it the proton collision or the distant galaxy. And at the same time we have tools at our disposal to evoke concepts of possible imaginings.

I’m interested in the difference between presence and the wandering mind. Between technological time and “real time”. I’m interested in being aware of our perception as it occurs. And, like one of the characters in the film says, referring to a quote by Teilhard de Chardin, I like the idea that “we are nature learning about itself”. All these ideas and more are folded into that sequence, but it will mean a lot of different things to different people, I’m sure!

The film ends with a very personal moment, which is quite unexpected. How do you conceive of your presence in the film? Why or how did you arrive at this as an ending?

When everything is said and done, when all the philosophy and physics and thinking is over, we still really only have our day-to-day experience to guide us. Our most concrete experience of time is: “We grow old, we die”. This is the basic way we know time acts upon us. I’m just a filmmaker making a film, using a time machine to ponder time. This is my reality and there is no elaborate fiction to hide behind. At some point in this journey we must acknowledge our elders. In the end, we are forced back to basics. As mothers have said to their children for countless eons: “Make the most of your life, because it will pass.”

Toronto, Canada – July 20, 2012

CREDITS

A maximage / Grimthorpe film in co-production with the National Film Board of Canada, SRF, SRG SSR, ARTE G.E.I.E.

Cinematography, writing, editing, sound design: Peter Mettler

Editing: Roland Schlimme

Story Editing: Alexandra Rockingham Gill

Sound Design: Peter Bräker

Original music: Gabriel Scotti and Vincent Hänni

Sound mix: Florian Eidenbenz, Magnetix

Picture Design: Patrick Lindenmaier, Andromeda

Additional camera: Camille Budin, Nick De Pencier

Location sound: Steve Richman, Mich Gerber, Dominik Fricker

Producers: Cornelia Seitler, Ingrid Veninger, Brigitte Hofer, Gerry Flahive

Associate producer: Tess Girard

Executive producers: Peter Mettler, Silva Basmajian

AWARDS

Premio Qualita di Vita Award, Locarno Film Festival

Masters Selection, Toronto International Film Festival

Opening Night Film, RIDM

Opening Night Film, Imagine Science Film Festival

Best World Documentary, Jihlava International Documentary Festival

Canada’s Top Ten List 2012

Nominated for Best Documentary, Cinematography, Score, Swiss Film Awards